An interview with MidCentury Home magazine and the home’s trustee. The owner grew up in this Streng, lives in an Eichler in the Bay Area, and has cared for this home for the past five years. Here’s his perspective on what makes it special.

The Ultimate Streng Bros. Modern Home

Preserved and Perfected.

A 1977 Carter Sparks-designed Streng with custom interiors by Larry C. Fernandez

Woodland, California

• • •

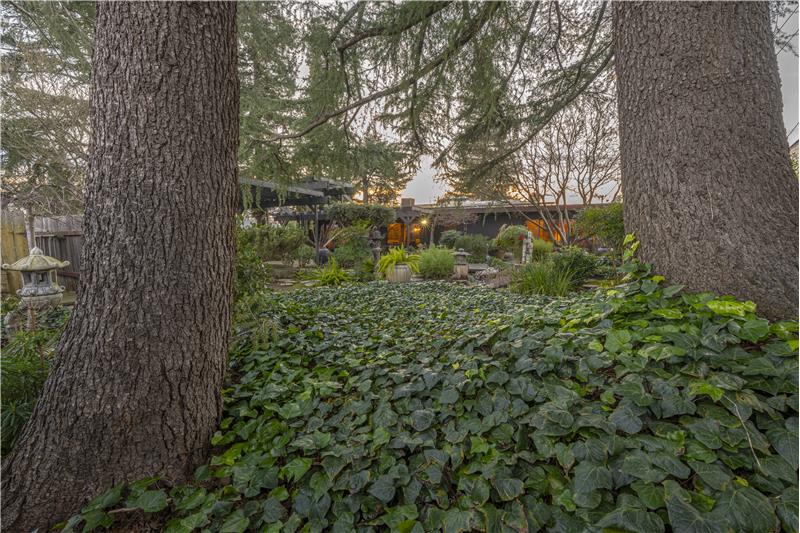

The entry path through mature junipers and Japanese-inspired plantings.

What do you remember about your parents first choosing this Streng Bros. home in Woodland, and what made it feel like the right place for them?

We already knew we loved the Streng way of living. My parents had built a semi-custom Streng on American River Drive in Sacramento in 1972, working with Jim and Bill Streng and my uncle, the interior designer Larry C. Fernandez. I was six years old for that one—I remember sitting on my mom’s lap next to my dad and Larry, across the desk from the Streng brothers, reviewing plans. They were wonderful to work with, open to every idea.

When my father retired from the Air Force and took a position as Director of Finance for the City of Woodland, we knew exactly what we wanted. By then I was ten, and we were back at that same table with the Streng brothers, only this time we knew what to improve. Additional custom windows to soften the corners. Upgraded finishes throughout—ceramic tile counters and Japanese textured flooring instead of the standard Streng spec. And because this was our forever home, Larry designed a far more ambitious landscape: a Japanese-inspired zen garden with a dry creek, massive, shaded patios, and plantings of redwood and cedar that are now nearly fifty years mature.

The indoor-outdoor character is what sold us the first time—the covered atrium, the walls of glass, an open floor plan that still gives you privacy. But this house took all of that and elevated it. My mother never wanted to live anywhere else.

• • •

The enclosed atrium with fourteen-foot palms reaching toward the skylight.

Your uncle, Larry Fernandez, played a major role in shaping the interiors. How would you describe his design sensibility, and where do you still see his hand most clearly today?

Larry used to say his work was about “comfortable drama and illusion.” He could invoke moods and other places through design alone. His specialty was modern environments filled with antique Asian art and natural elements—Japanese garden design was his deepest influence, and he brought that sensibility indoors.

His signature move was the dry creek. Ours starts at the enclosed entry, runs through the indoor atrium alongside exposed aggregate walkways, continues out through the backyard, and disappears behind a berm at the far end of the lot—so you always feel the creek keeps going, out into the landscape beyond. He’d sometimes hide a small bubbling fountain just out of sight, so you’d swear the creek actually had water. He also used lighting in unexpected ways—he might install a skylight and place bamboo inside it so it appeared to be growing up through the roof. In this home, he selected palms to reach up to the solar dome for the same effect.

The black glass wall in the dining area is pure Larry. It’s a literal wall of black glass, reflective like a dark mirror. It makes the dining space feel intimate and theatrical even though there’s no partition on the other side—you’re sitting in the open living area, but the glass creates its own room. With candles lit at dinner, it’s stunning.

Larry was a professional designer—he was working with the Sacramento firm Miles Treaster Associates when this house was designed, and his other projects were featured in Architectural Digest, Interior Design, and Designer’s West. He passed away young, at thirty-eight, but his work lives on in every room of this house. I keep his archives, so the provenance is documented down to the last detail.

• • •

The centrally placed kitchen with original walnut cabinetry and modern Bosch and Electrolux appliances.

This home began as a classic atrium model, but with thoughtful changes for flow, windows, and finishes. What were the most meaningful departures from the original Streng spec?

The biggest change was flipping the kitchen and formal living area. In the standard plan, the kitchen was tucked in a corner. Larry moved it to the center of the house, with the backs of the cabinets forming a partial wall that cleverly screens the atrium from the workspace. It gave my mother a command center—she was a teacher, and she’d sit at the dining-table-level counter to grade papers, cook, keep an eye on us kids, and still feel connected to every part of the house. She was closer to the private wing this way, with the TV snug, utility room, and bedrooms all within easy reach.

Larry also specified additional windows during construction to soften the architectural corners, including a floor-to-ceiling front door flanked by full-height glass panels—so the entry itself is a moment. And he gave planting guides to take full advantage of the fourteen-foot atrium, which is why the palms in there are still thriving and gorgeous after nearly fifty years.

But the real magic is in the consistency of the finishes. A lot of homeowners mix materials room to room, and it makes a house feel smaller. Larry used the same warm cabinetry throughout the kitchen and bathrooms—slab-panel in a rich walnut finish—and carried the same beige tile on every counter. The Japanese textured floor tiles match the intensity of the exposed aggregate in the atrium, so everything reads as one continuous surface. The exposed redwood beams in their original Mission Brown stain provide the structure. It all works together as a single composition, and that’s entirely Larry’s discipline.

• • •

Over twelve hundred square feet of patio space beneath pergolas and a canopy of mature redwoods and cedars.

The landscape sounds as intentional as the architecture, with pergolas and shaded outdoor rooms designed for the Central Valley climate. How did your family use those spaces day to day?

Larry designed the landscape as well—he was also a landscape designer, and Japanese garden principles were central to his approach. My mother was the one who made it come alive, though. She was an excellent gardener, and the two of them studied Japanese garden design together. There’s even a tea ceremony rock placed near the dry creek.

When the weather was nice, and in Woodland, that’s almost all of the year, we moved in and out seamlessly. We’d eat dinner at the outdoor table under the shaded overhang just outside the kitchen as often as we would indoors. My dad would take his morning coffee out into the garden to watch the squirrels and blue jays—he had many favorite spots depending on the season, the light, his mood. There are over twelve hundred square feet of exposed aggregate patio in the back, with about half covered by pergolas. These are recently rebuilt to the original designs with alternating boards that filter the light and create a feeling of enclosure without closing you in. Some extend directly from the roofline; further into the garden they become freestanding structures, ten to twelve feet tall.

Woodland has the prettiest winters of anywhere I’ve been, with this soft misty light from the tule fog that lasts much of the day, and the house makes the most of it. With the long wall of sliding glass doors facing east into the mature garden, it feels like a Japanese tea house. You’re warm inside, looking out through the glass at the redwoods and cedars, the sculptural junipers, the stone lanterns. The trees are nearly fifty years old now, well maintained by arborists, and the canopy they create is extraordinary. The front is shielded by mature junipers six to eight feet tall that provide screening and privacy while still feeling open and welcoming.

• • •

The family room opens onto the atrium and garden through east-facing glass.

You’ve kept the house remarkably original while updating systems like solar and heat pumps. How did you approach modernizing without losing the home’s mid-century spirit?

The original design was flawless—we didn’t do anything to change it. Every modern upgrade is invisible. The rooftop solar is invisible from inside and out. The foam roof is invisible. The heat pump water heater just looks like a slightly larger appliance. We upgraded all the recessed lighting to LED, but the enclosures are a perfect match for the originals. New stainless Bosch and Electrolux appliances in the kitchen, induction cooktop—that was the only tricky moment, actually, because induction required a different breaker, but otherwise it’s remarkable how easy every upgrade was. My parents had wired the house exceptionally well from the start.

There’s a clever detail I love: the entry closet, which in most homes would hold coats, is wired as a media hub. Cable, Wi-Fi, and speaker wire all run from that closet to speakers throughout the living areas, so you can have music in every room with no visible wires. That was forward-thinking in 1977.

For the last five years I’ve been here every other week looking after my mother, and I’m the one who handled most of the upgrades—maintaining the floors and cabinetry, modernizing the electrical, keeping everything in the condition it deserves. It was never a question of reinventing. It was a question of honoring what was there.

• • •

The full-height entry with floor-to-ceiling glass panels.

As you prepare to sell after your mother’s passing, what do you hope the next owners will understand or appreciate about living in a house with this much family and design history?

It’s rare to find a home that is both maintained in its original condition and genuinely updated where it matters. So many mid-century homes have been painted white or “renovated” in ways that erase what made them special. I used to give tours as a docent at the Gamble House in Pasadena, the great Greene and Greene arts-and-crafts masterpiece, and there’s a story in the house’s history about how it was nearly sold in the 1960s until the family heard a prospective buyer say they would paint all that incredible woodwork white. They pulled it off the market.

I live in an Eichler home myself now, and growing up in this Streng is a big reason why. I’ve given the same advice to my neighbors in our Eichler tract, and they’ve always thanked me for it later: move into an architecturally significant home and don’t do anything for six months. Just live in it. See what the morning light does. Watch the garden through a full cycle of seasons. Discover what you love and then figure out what needs to change for your particular life.

The biggest mistake I see with Streng homes is people not understanding the atrium—they fill it in, or they try to turn the house into something it isn’t. These are the ultimate machines for living. They’ll adapt to almost anything, but you need to understand how they work first. And trees—don’t underestimate what mature trees and proper shade do in the Central Valley. They make a garden comfortable year-round.

The front of this house faces west with no windows, screened by trees and junipers, so it stays cool. The wall of glass in back faces east, and while the pergolas block the high sun, those first warm rays of morning are gorgeous. The atrium skylight diffuses sunlight all day long. The house is always beautifully lit but never harsh.

Ultimately, this is a story about stewardship. If you’re a good steward of your home, it will be a good steward of you. This house brought our family a lifetime of joy. It’s time for it to serve another generation, and it’s a real opportunity for someone who loves architecture, elegant living, and the idea of living in a work of art to find not just a house, but a home.

• • •

Photography by David Allen